US tests strategies to interest girls in computer science

Simply sign up to the Technology sector myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

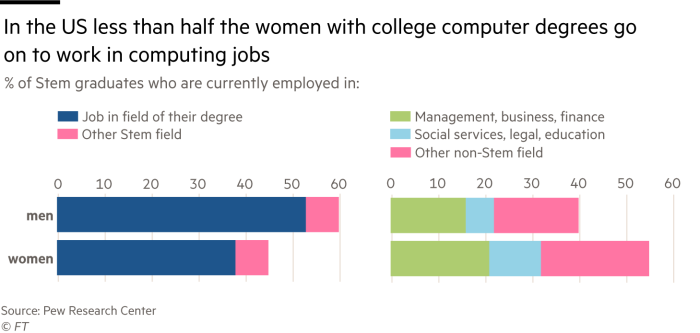

As the technology sector works to solve its diversity problem it must grapple with a puzzle: why fewer women studying computer science?

Today, less than 20 per cent of computer science graduates in the US are female, compared with more than a third in the mid-1980s.

“You don’t see the same gender disparity in other in other sciences as you do in computer science,” says Reshma Saujani, founder of Girls Who Code, a non-profit organisation that runs after-school clubs across the US for girls up to 12th grade (age 18). “There’s much more gender parity in biology or [maths] than in computer science.”

To address this, researchers and educators are testing new strategies and curriculum tweaks to make computer science more appealing to women.

Linda Sax, a professor of education at the University of California, Los Angeles, is leading a research team that received a $2m grant from the US National Science Foundation to study diversity in computer science education at university level. A key question, she says, is how to make introductory computer science accessible, because new students come from a wide variety of backgrounds.

“We know that women come in [to college] with much less preparation in computer science specifically,” she says. This could be addressed by offering different sections of an introductory course based on students’ prior experience, she says, or by using inclusive teaching practices, such as working in pairs, to help students build a sense of belonging.

Curriculum design could also make a difference. “If you teach computing that is just focused on programming, you will attract some students, but to generate a diverse group — [with men from more diverse backgrounds] as well — it is important to emphasise how computing makes a difference in society,” says Prof Sax.

Other organisations are addressing diversity in computer science education before students even get to college. Code.org is a non-profit body that runs the largest computer science teacher-training programme in the US for K-12 schools (kindergarten to high school).

Diversity informs all aspects of the programme, including teachers being trained to recruit a diverse range of students — for example, if only one girl signs up for a class, the teacher might encourage her to invite a few friends.

The curriculum is also designed to be accessible to students from diverse backgrounds. Rather than starting with coding, the programme’s middle school and high school classes begin with logic and data, which helps create more of a level playing field in the classroom.

“If you start with coding, those who already know it accelerate super fast, and those with no background feel they are not good enough,” explains Hadi Partovi, Code.org founder and chief executive.

“That’s a really simple thing, but it makes a meaningful difference in attitudes. The curriculum is designed with equity and diversity in mind.”

The attention to diversity even extends to classroom decor. Code.org gives teachers posters to put up that show people from all walks of life, says Mr Partovi. “Just to make it less about the robots and more about humanity.”

These steps taken by Code.org — which trains teachers for more than a third of advanced computer science courses in the US — seem to be making a difference. In 2017, girls accounted for 27 per cent of students on advanced computer science courses in high school, compared with 20 per cent in 2014. The numbers have been boosted in part by the addition of a second type of college-level computer science exam, which focuses more on computer science principles than on coding.

That makes a big difference when students get to college, where women are 10 times more likely to major in computer science if they have done an advanced placement course at high school, according to a Code.org analysis of data from the College Board.

The ratio of female college computer science graduates is also inching up. Women accounted for 18.7 per cent of college computer science graduates in the US in 2016-17, compared with 18 per cent the previous year, according to the US National Center for Education Statistics. That is still far below the peak of 1983-84, when women comprised 37.1 per cent of computer science graduates.

When it comes to changing the culture in Silicon Valley, though, educators are well aware that drawing more women into computer science is just the first step.

“Just because we bring more women into computing, that doesn’t necessarily change the culture,” says Prof Sax. “It takes a lot to change the culture in the industry.”

It is a chicken-and-egg problem: a lack of diversity in the tech industry discourages women from studying computer science, which in turn makes it harder to recruit engineers from more diverse backgrounds.

“Obviously the education pipeline isn’t the only problem with diversity in tech,” Mr Partovi says. “But it’s a core piece, and it’s for sure changing.”

Comments